Nytimes When Is It Safe to Eat Romaine Again

Introduction

Nosotros were delighted as our 12-year-old grandson ordered a Caesar salad when we were having dinner at a pizza place. Vegetables! However, the dinner was December 22, 2019, shortly after CDC and FDA issued yet another warning against eating romaine from Salinas, California. I asked the server where the romaine came from. He didn't know just went in the dorsum to inquire. He returned and said, "Salinas."

Since 2017, seven outbreaks involving romaine lettuce have sickened hundreds and killed five. Those are the reported numbers. No one knows how many other people got ill. In six outbreaks the lettuce came from California's Salinas Valley region; in the seventh from the Yuma, Arizona region, which includes California's Imperial Valley. Repeated FDA and CDC warnings against eating romaine have left consumers adrift in a sea of confusing announcements, advisories, and recalls. Is romaine safe to swallow?

Between November and March, almost all of the country'south romaine, iceberg, red leaf, green leaf, arugula, broccoli, and cauliflower (collectively known every bit leafy greens) comes from the Yuma region. During the rest of the yr, leafy greens are grown in the Salinas region. The ii states produce 98 percent of the country'due south lettuce. Anyone who eats salad or likes lettuce on their Big Macs or tacos is personally impacted by how lettuce is grown and candy.

Most consumers will be surprised to learn what happens to their lettuce earlier they bring it domicile from the supermarket. Between lettuce farms and the ultimate consumer is a remarkable system of steps taken by farmers and processors to protect the prophylactic of leafy greens. If an outbreak does occur, federal and state regulators employ an elaborate network of laboratories to identify the source of the contamination.

As a event, the chances of getting sick from eating leafy greens in America are minuscule. To put the risk in perspective, consider that California and Arizona farmers produce an estimated 130 million servings of leafy greens every solar day of the twelvemonth.

Consumers should take condolement in knowing that farmers and processors, in response to the recent outbreaks, accept implemented fifty-fifty more stringent standards. That said, at that place are inherent risks in eating raw food that is grown outdoors. The arrangement is not and never will exist perfect.

"I Wouldn't Wish This on My Worst Enemy"

On March 20, 2018, Louise Fraser, a 66-yr-former woman from Flemington, New Jersey, ate a Fuji Apple tree Chicken Salad at a Panera Restaurant in Raritan, New Jersey. Over the side by side few days, she experienced astringent tummy cramps, nausea, vomiting, headache, and a fever. When her diarrhea turned bloody, she went to the emergency room at Hunterdon Medical Center. On March 25th, the medical team admitted her and began a battery of tests. Laboratory tests confirmed she was infected with E. coli O157:H7, which caused hemolytic uremic syndrome, a condition that can lead to kidney failure and decease. It took 13 days of medical supervision and three blood transfusions to save her life. She calls the infection "the worst feel of my life. I wouldn't wish this on my worst enemy."

Louise became ill from an outbreak of E. coli O157:H7 traced to romaine grown in the Yuma region. The outbreak killed five people, hospitalized 96, and sickened 240 in 36 states, before ending in June 2018, making it the largest outbreak of this particularly nasty strain of E. coli since 2006.

Infectious Diseases and Food

Guide books warn travelers to third-earth countries not to beverage the water or eat raw vegetables for skilful reason. Due to the lack of adequate sanitation, the water is often contaminated with human or beast fecal matter, and farmers often use that water to grow vegetables.

Pathogens, including bacteria, fungi, and viruses, cause infectious diseases. E. coli O157:H7 most often occurs in the intestinal tracts of farmyard animals, especially cattle, sheep, pigs, and poultry. The animals endure no symptoms, but they serve equally carriers that shed bacteria in their feces, which tin can end up in the water supply. People can get ill from drinking contaminated h2o, merely nearly E. coli infections come from eating food irrigated with the contaminated h2o.

Dozens of Eastward. coli outbreaks associated with leafy greens accept occurred since 1995. The worst i, in 2006, involved baby spinach that came from an organic farm in California's Salinas Valley. That outbreak prompted the California and Arizona lettuce industries, in 2007, to enter Leafy Greens Marketing Agreements (LGMAs), which require members to comply with science-based guidelines for producing and harvesting leafy greens.

In 2011, Congress passed the Food Rubber Modernization Act (FSMA), which adopted the best practices of the LGMAs. The Act strengthened the nutrient prophylactic system by broadening FDA's authority and requiring FDA to promulgate scientific discipline-based, minimum standards for the safe production and harvesting of fruits and vegetables.

Growing Lettuce: Food-Safety Challenges

Lettuce farmers face up food-safety challenges greater than other nutrient producers. Pasteurizing, irradiating or cooking kills pathogens in almost foods. But there is no "kill step" for lettuce, which is grown outdoors, not in a controlled environs like a factory or a greenhouse, and eaten raw. Paul Brierley, head of the Yuma Center of Excellence for Desert Agronomics, describes farmers' struggle against E. coli O157:H7 every bit "fighting an invisible, tasteless, odorless enemy."

I first took students in my class, The Colorado River, on a field trip to Yuma in 2016. We met with a prominent farmer at his headquarters to learn about "food safety." If a flock of geese fly over the farmer'southward field, or a domestic dog or deer wanders in, they may go out backside droppings with E.coli and other unsafe microbials. To monitor such intrusions, he keeps meticulous records of every occurrence and the response by engagement, time, and location. On his big briefing room tabular array, stacks of binders chronicled nutrient safety steps from preparing the fields each flavor through planting and harvesting.

Nutrient safety, whether in Salinas or Yuma, starts with a pre-harvest inspection of fields and fertilizers. As anyone with a backyard garden knows, manure helps things to abound. But it'south risky to utilise around vegetables. Before harvesting, nutrient safety auditors (employed by shippers non growers) review a farmer's policies and records, conduct a visual inspection of fields for signs of beast intrusion, and verify the practices are in place. The last step before harvesting involves taking samples from plants and sending them to a lab for testing. The usual practise is N60 or 60 samples in a five-acre plot.

Harvesting crews piece of work for packing companies and follow elaborate nutrient safety practices. Exterior each porta-potty is hand sanitizer. Pickers wear gloves, masks and gowns, depending on whether lettuce is to be sold "naked" or candy. Workers cannot wearable jewelry other than wedding bands or carry anything in their upper pockets. Every picker's tools are numbered.

When crews harvest romaine for processing, they cadre and make clean each head and place them bottom side up in boxes. They spray the boxes with water mixed with sodium hypochlorite and non-iodized salt to wash off latex, a naturally-occurring and harmless white-milky sap that oozes from the cuts. The spray helps to sanitize the cut surface, close the plants' wounds, and prevent browning.

From Farm to Consumer

Harvested lettuce intended for processing is starting time sent to refrigerated warehouses, and vacuum cooled to 33-38 degrees F. At the processing establish, workers chop and shred the lettuce, which is sorted into unlike wash lines, for instance, romaine in 1 and spinach in another. It'south commonly triple-washed in flumes, each time with fresh water. Automated controllers inject sanitizer into the flumes for the first and 2nd washes. The sanitizer prevents bacteria, such as Eastward. coli O157:H7, that washes off a leaf from cross- contaminating other leaves during the washing bicycle. The tertiary wash involves a beverage h2o rinse.

The done lettuce is dried in large stainless-steel barrels using centrifugal forcefulness. Imagine a salad spinner that holds 300 pounds of lettuce. A machine and so lifts the barrels and dumps the lettuce into a hopper, which feeds a conveyor belt to a scale, shaped like a cone with a bunch of buckets around it. A computer controls the buckets to mensurate the correct weight for each bag, depending on the client's needs.

Workers dorsum-affluent the numberless with nitrogen to control the amount of oxygen in the bag. Processors use modified atmosphere packaging. I recall of lettuce bags at my local Safeway as "plastic numberless," but processors regard them as oxygen transmission charge per unit (OTR) film. 1 processor'southward food prophylactic director (who asked me non to use his name, and so we'll call him John Doe) explains that "the OTR flick is specific for each blazon of lettuce and allows for an commutation of gases between the within of the bag and the outside." It allows just enough oxygen to induce the lettuce to go dormant. The lettuce remains in that country as it travels around the country until the bag is opened at a restaurant or a home.

Each bag is vacuum-sealed, run through a metal detector and hand-packed into boxes. At some processors, an inkjet printer stamps a characterization on every purse and box. Each label, explains Doe, "has a unique code with the product date, plant code, pack line production shift, the stock-keeping-unit of measurement (SKU) lawmaking, and a timestamp down to the second." Workers place the boxes on pallets and load them onto refrigerated trucks.

Processors typically clean the entire institute every day. "Sanitation for u.s.a. is the nigh important office of the solar day," says Doe. "A crew of xx cleans every chugalug, piece of cutting equipment, floors, drains, walls, everything. The procedure starts with a dry pick-upward then a rinse, and the application of chlorinated alkaline lather. Workers cream and scrub the areas that need it, and terminate up with a final sanitizer, either peracetic acid or quaternary ammonia. That'southward washed every nighttime." On weekends, he explains, they shut the constitute down for "a deep clean period, from Sunday into Monday, when we do preventative maintenance that we can't get done during the week."

Shipper-processors sell to eating place and grocery chains and foodservice companies, such equally Sysco, which delivers to schools and hospitals. In a matter of hours or days, lettuce arrives at grocery stores around the state. Ironically, consumers may exist the weakest link in the produce nutrient safety system. What practise yous put on the seat in your grocery cart? Until recently, I put produce. Now I'm haunted by the paradigm of the concluding customer's dog, toddler, or purse. Once home, many consumers put lettuce into the sink or on a counter — two places loaded with leaner.

A Mystery Fit for CSI

In early Apr 2018, the New Bailiwick of jersey health department contacted CDC nigh a cluster of Eastward. coli O157: H7 infections. Many of the sick people had eaten salads at restaurants before condign sick. In subsequent days, according to Dr. Laura Gieraltowski, an epidemiologist who heads CDC'southward Foodborne Outbreak Response Team, "illnesses with the same Dna fingerprint were uploaded to CDC's PulseNet database — indicating a potential multistate outbreak."

PulseNet is a national network of 83 public health and food regulatory laboratories that submit samples of harmful bacteria from infected patients. FDA likewise employs another network, GenomeTrakr, which sequences the genomes of foodborne pathogens and uploads information to a publicly-attainable database. The two systems office symbiotically, ane generating information about patients, the other nigh nutrient.

Like a police detective looking at pins on a board in a murder investigation, Dr. Gieraltowski's team looks for points of convergence from clusters of illness with a mutual indicate of exposure, such equally a restaurant. FDA'south network of specialists tries to effigy out the origin of the contaminated food. Their approach is to motility backward from sick people through the food distribution organization to the original supplier. This procedure, called a traceback, was exceedingly challenging in the April 2022 romaine outbreak.

Romaine is a perishable commodity with a short shelf life. By the fourth dimension people get sick, physicians and clinics report their cases, laboratories test the specimens and fingerprint the pathogen, and wellness officials interview the sick people, the shelf life is over. Based on interviews with patients, clinical laboratory results, and Dna fingerprinting, FDA announced on April xiii, 2018, that "the likely source" was farms in the Yuma growing region.

In June 2018, FDA investigators inspected farms, interviewed farmers and processors, and contacted cattle feeding operations and water districts. FDA teams were searching for the root crusade of the outbreak. CDC'due south National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS) laboratory used Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) to determine that irrigation water from a Wellton-Mohawk Irrigation and Drainage District canal shared the same rare molecular fingerprint every bit the O157:H7 that infected the sick people. FDA found no other evidence of the presence of O157:H7.

To pinpoint precisely which farms and fields provided the romaine, investigators would demand samples to exam. However, by the time the FDA team arrived in Yuma, the romaine flavour had ended, the farm equipment cleaned and stored for the next flavor, and the processing plants closed down. There was no romaine to test. FDA did identify one farm that sent whole-head romaine to an Alaska prison where eight inmates got sick. In that example, the farm was the sole source supplier, simply it did not cause the nationwide outbreak.

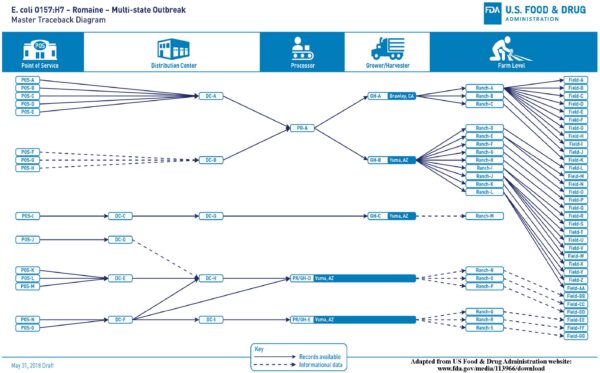

On November i, 2018, FDA's Environmental Assessment concluded the romaine came from the Yuma region. The traceback identified 36 fields on 23 farms that supplied romaine "that was potentially contaminated." (Emphasis added). As seen on the Traceback Diagram (next folio), multiple farms sent romaine to each processor, where the product became commingled as information technology was washed, dried, packed, and boxed. Distributors, in plough, received romaine from more than one processor. The commingling, FDA admitted, "made it impossible to definitively determine which farm or farms identified in the traceback supplied romaine lettuce contaminated with the E. coli O157:H7 outbreak strain." That's 1 reason why, on the Traceback Diagram, FDA redacted the names.

FDA's assessment of the Yuma outbreak ended that "the most likely style" romaine became contaminated was from the Wellton-Mohawk irrigation canal h2o because that's the simply place FDA plant East. coli O157:H7. How did East. coli become into the h2o? FDA suspected the source was an adjacent Concentrated Brute Feeding Performance (CAFO). The V Rivers Cattle, LLC feedyard in Wellton, Arizona, about 30 miles e of Yuma, can business firm more than than 100,000 head of cattle at a time.

FDA Traceback Diagram

I asked Bill Marler, a leading food safety attorney, what he thinks caused the outbreak. Marler said the reply is obvious if you expect at an aeriform photograph of the CAFO shut to the canal. "It doesn't take a rocket scientist to figure out the likely source of O157 in the Yuma valley. It's moo-cow shit." He is inappreciably alone in reaching this conclusion, though several people expressed their views off-the-tape. Manure is a vexing problem for feedlots: each steer tin can produce 65 pounds per mean solar day, most of which is water.

Nagging doubts remain. For example, if canal h2o contaminated romaine, why did it not as well contaminate baby leafage, spinach or leap mix, which are irrigated with the aforementioned water. If culvert water did not contaminate romaine leaves, is in that location another explanation? FDA ruled out wild animals because O157:H7 is an antibiotic-resistant strain, suggesting it came from the scat of domestic animals, who were inoculated or given feed with antibiotics in it.

FDA inspectors sampled soil, wild and domesticated animal scat, biological fertilizers, surface and subsurface water, irrigation water from the Colorado River, and sediment from irrigation canals. In the end, only 3 samples from the Wellton-Mohawk canal tested positive.

FDA also considered unusual weather patterns, including a hard freeze in Feb 2022 and strong winds in March 2018. The common cold temperatures blistered romaine leaves, making the crop more susceptible to microbial contagion. High winds possibly carried contaminated soil particles and romaine — with creased, upturned leaves — may exist more vulnerable to trapping airborne particles. Aerial applications of pesticides could take caused the trouble if the water used to dilute the chemicals was contaminated. Perhaps a pesticide applicator drew water from the irrigation culvert and and then sprayed fields with contaminated water.

FDA best-selling these other theories just found no evidence to support them. The bottom line is that Wellton-Mohawk canal water tested positive for E. coli O157:H7, which commonly occurs in cattle, and a giant feedlot was located next to that canal. The rest is inference.

Outbreaks in November and Dec 2022 acquired by lettuce from Salinas spawned another plausible explanation for the root crusade, which focuses on timing. Six of the seven outbreaks since 2022 occurred toward the terminate of the romaine flavour, whether in California or Arizona. When farmers rotate their crops, they often spread manure or composting materials in advance of planting — at a time when romaine is still in the footing in neighboring farms. Perhaps current of air or water spread East. coli to the romaine fields.

A May 2022 FDA report on the Nov and December 2022 outbreaks concluded that "a potential contributing factor [was] the proximity of cattle to the produce fields." The report was not referring to a massive CAFO but cattle grazing on public land on nearby hills — equally far away as two miles from the romaine fields. This should send a shudder through ranchers and farmers across the Westward because the bucolic image of cattle grazing on a hillside is frequently visible from low-lying farms.

"We Don't Know Exactly What to Gear up."

In Apr 2018, before FDA investigators arrived in Yuma, the leafy greens manufacture established job forces to examine current practices and suggest reforms. For example, harvesters now clean and sanitize the equipment daily. Farmers and processors changed many practices, hoping that one or a combination would have an bear upon. "Just we only don't know," explained John Doe, the food safety director. "And that'southward the really frustrating thing for everybody. Our customers and really the entire U.Due south. public wants us to fix it, set up it, fix it. And nosotros don't know exactly what to fix." Nonetheless, one processor decided to end buying from farms within a mile of a CAFO. That processor also changed its pre-harvest sampling methodology from sampling five-acre plots to sampling every acre.

In 2019, the Leafy Greens Agreements began to require growers to treat all surface water used inside 21 days of harvest. (Before that, sunlight exposes vegetables to plenty UV radiation to impale almost all dangerous pathogens.) Dr. Jennifer McEntire, vice president of nutrient safety for United Fresh Produce, a merchandise association, describes this change as "a primal shift" from testing water on an annual footing to "proactively treating water during the period closest to harvest."

"Food Traceability @ the Speed of Idea"

On November i, 2018, FDA so-Commissioner Scott Gottlieb chosen for the industry to standardize record-keeping and to use labels or other tools to ameliorate traceability. Nutrient condom records on many farms are hand-written notes. Some bags and boxes have labels that place the variety, grower, field, and harvest date; others don't. The lack of a uniform standard creates problems for fast traceback. United Fresh Produce'south Jennifer McEntire supports improved labels. "If we have true traceability, we could

pinpoint exactly what the problematic production was, who produced it, and when. We wouldn't demand a wide advisory." Labels on romaine at present include the growing region (Salinas or Yuma), which enabled FDA in November 2022 to limit its consumer warning to romaine from Salinas.

In December 2018, Frank Yiannas, a renowned nutrient condom expert at Walmart, became FDA Deputy Commissioner for Food Policy and Response. At Walmart, Yiannas used blockchain, the all-time-known type of digital ledger technology, to track mangos from two farms in Mexico to two stores in the U.s.a.. In a pilot projection, each participant in the supply concatenation put data on the blockchain, which linked the blocks of data and reduced traceback time to two.2 seconds. Real-time traceability is the holy grail to Yiannas, who refers to information technology equally "food traceability @ the speed of thought."

In April 2019, Yiannas and FDA Acting Commissioner, Ned Sharpless, M.D., announced that FDA would enter a New Era of Smarter Nutrient Safety, anchored past moving from largely newspaper-based information to a digital organization, such as FedEx, Uber, and Amazon apply to track the movement of trucks, ride sharing and delivery of packaged appurtenances. The new era arrived in July 2022 with FDA's Blueprint for Smarter Nutrient Rubber, which will encourage and incentivize the leafy greens industry to adopt tech-enabled traceability measures. The labels on bags and boxes of lettuce may soon accept data stored on the cloud or blockchain.

Only labels tin can better traceability but if data gets saved. No thing how remarkable digital ledger technology is, it will promote traceability but if the shipping/receiving clerk at a restaurant or a supermarket scans the labels when the boxes arrive. Yuma farmer John Boelts notes that traceability breaks down in "the terminal mile to the consumer," when supermarket workers or dwelling cooks throw abroad the bags and boxes. At a public meeting on the New Era that FDA hosted in October 2019, Yiannas best-selling this trouble: "What matters most is what people do." The behavior of anybody in the nutrient industry, from farmers to servers, will ultimately determine the safety of our nutrient.

In September 2020, FDA announced a proposed rule regulating recordkeeping that would crave the leafy greens industry to go on records with Critical Tracking Events and Fundamental Data Elements. Prompt traceability requires three atmospheric condition: uniform labels, interoperable data collection and storage, and unanimous participation past growers, processors, shippers, and buyers. Although this rule has many exemptions, it would go a long style toward creating those conditions.

Compatible labels and effective digital storage could dramatically reduce traceback times. Better data volition not preclude the initial consumers of contaminated produce from becoming sick, but it could limit the calibration of an outbreak by speedily determining the source of the contamination. Other electric current research is directed at prevention past achieving real-time detection of pathogens before the lettuce ever enters the food concatenation. Paul Brierley, caput of the Yuma Centre of Excellence for Desert Agriculture, has a inquiry project involving biosensors, which would enable farmers to detect pathogens in water or in the processing plant. Brierley concedes: "We accept a long way to go."

In October and November 2020, FDA announced an investigation of 3 new outbreaks of E. coliO157:H7. Its traceback investigations were unable to make up one's mind a common source of the outbreaks.

What Should Consumers Exercise?

In the meantime, consumers face up hard choices. They certainly should not stop eating romaine and other leafy greens. Nutritionists concord that we should swallow more fruit and vegetables.

Consumers may choose to launder all lettuce, even the bagged and boxed mixes. Despite the elaborate precautions taken past processors, contaminated romaine made its way into the distribution arrangement. In Nov 2018, FDA warned that washing "may reduce but will not eliminate [E. coli O157:H7] from romaine lettuce." Despite this warning, I don't plan to first washing lettuce that has already been triple washed.

Consumers accept other choices, including ownership organic produce. But it is worth remembering that the 2006 E. coli O157:H7 outbreak involved spinach from an organic farm. Other consumers may prefer to buy greenhouse-grown lettuce, which has non been implicated in contempo outbreaks. Just lettuce grown indoors is a niche market, not 1 capable of producing tens of millions of servings a day. Yet others may desire to buy from farmers markets. But information technology is unclear whether that lettuce is safer than candy lettuce from California or Arizona. Plus, few farmers markets are open from tardily fall through winter, which is the Yuma flavour. If you want lettuce during those 5 months, information technology's going to come from Yuma.

When bad things happen, Americans expect that someone or something is to blame. Nosotros desire everything to be perfect, whether it's a medical process, a machine repair, or the food we eat. However, no amount of testing and treating will completely eliminate the risk of getting ill from eating raw something that is grown outdoors.

Source: https://robertglennon.net/is-romaine-safe-to-eat/

0 Response to "Nytimes When Is It Safe to Eat Romaine Again"

Postar um comentário